Adolf Hitler standing in his car as he travels through

By

Professor Duncan Anderson

BBC.co.uk

Adolf Hitler standing in his car as he travels through

Towards the end of World War Two, the British Special Operations Executive considered an attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler - an attempt that was never made. Duncan Anderson considers what might have happened if Operation Foxley - as the plan was named - had gone ahead, and had succeeded.

Adolf Hitler was the centre of the Nazi system. Around him revolved a loose confederation of fiefdoms, whose leaders engaged in a ceaseless struggle to protect and enhance their power. If Operation Foxley, the plan devised by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) to assassinate Hitler, had succeeded, this system would have been thrown into chaos.

Count von Stauffenberg and various fellow conspirators, whose courage was equalled only by their ineptitude, were plotting a similar operation from the German side. There was, however, not the slightest possibility that they could have taken advantage of the chaos.

German Nazi leader, Hermann Goering, speaking at a rally c. 1943 ©

German Nazi leader, Hermann Goering, speaking at a rally c. 1943 ©

Rather more likely was the

emergence of a coalition of the major fiefdoms, with Hermann Goering as Reichsverweser (literally state caretaker),

co-existing uneasily with Heinrich Himmler, Albert

Speer, Karl Doenitz and a clutch of popular generals

such as Erich von Manstein and Erwin Rommel.

The most plausible date for SOE's assassination of

Hitler would have been around 13-14 July 1944. By this time the Russians had

reached the old Polish-Soviet frontier. From what is now known about the frame

of mind of many prominent generals in

'The most plausible date for SOE's assassination of Hitler would have been around 13-14

July 1944.'

For Himmler and the SS even a negotiated peace would have posed serious problems. He would have been worried about how he was going to explain the 'final solution' (the extermination of all Jewish people, and other 'untermenschen', in Nazi-held territories) to the outside world, and might well have decided to close down the gas chambers, and tried to pass the death factories off as labour camps.

Germany

still in control of Europe

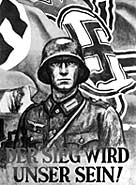

Nazi propaganda poster, showing a helmeted

soldier in front of swastika flags, with the slogan

in

German, 'Victory Will be Ours', c. 1942 ©

At

this stage, however, a reversal of policy would have been prudent rather than

pressing.

Moreover, the propaganda machine run by Goebbels

would have both lionised the martyred Führer - the modern Seigfried -

and hinted that with the Führer now in

'...

the propaganda machine run by Goebbels

would have both lionised the martyred Führer ...'

How would the death of Hitler have

affected the Reich's production of war material? Overall very little, except in

one important area. In June, Speer and Goering had

pleaded with the Führer to abandon the conversion of

the ME262 jet fighter into a bomber, but to no effect. With Hitler gone, the

Luftwaffe might have had twice as many ME262s available in the autumn of 1944,

not enough to establish air parity with the Allies, but enough to have made the

air war in the west less one-sided.

Hitler's death would have had a much

greater effect on the conduct of operations. On the Eastern Front, Erich von Manstein, Heinz Guderian and

others had already proposed withdrawal from the

A new line on the Front would have

emerged, running south along the heavily fortified border of

'With

Hitler gone, Margarethe II would have swung into

action ...'

The army already had a contingency plan, Margarethe

II, for the occupation of

Operations in the west, too, would

have been profoundly affected by the Führer's demise.

On 28 June Hitler had rejected a plan, put forward by von Rundstedt

and Rommel, which suggested a German withdrawal back

to the line of the

'The

early withdrawal from

Instead a defence

of the Seine would have been followed by a defence of

the Somme, and then the Meuse and

Hitler's demise, then, would have

allowed

'...

without Hitler there would have been no

Moreover, without Hitler there would

have been no

The disparity in production and

manpower between the Allies and

In our alternative world, it is

difficult to see how the Vistula -

On 23 January, Soviet forces reached

the Oder, only 60 miles east of

They hoped the Allies would thus be

drawn in to join with

'Goering and Himmler, now weak and

discredited, would have gone to the wall ...'

Would it have become policy? It is

possible, given that the crisis produced by the Vitula-Oder

offensive would have fractured the loose coalition running

Winston Churchill,

Winston Churchill,

The

But if the plan had been followed,

suddenly

If the Germans had taken the

initiative, and had begun pulling back from their western defences,

it is difficult to see how Anglo-American forces could have avoided being

sucked into the resulting vacuum, and pushing on to face the Russian advances,

no matter what political decision had been made in London and Washington.

By ending the war three months early,

The long-term political impact of the

way the war ended would have been immense if Operation Foxley

had succeeded. If it had, and Stalin had been excluded from the Balkans or from

'...

the Cold War would have started with a bang ...'

In this scenario, the Cold War would

have started with a bang the moment the Anglo Americans reached the German side

of the Eastern Front. In June 1945 Churchill, worried by increasing Soviet

belligerence, actually did propose the re- mobilisation

of German forces as a way of opposing Stalin, a suggestion that was quickly

buried by the chiefs of staff. In the post-Foxley

world, he may have got his way.

The spring and early summer of 1945

would have been the period of maximum danger, as Russian and Allied troops

faced each other. This confrontation would have eased only with the first

successful test of the American atomic bomb on 16 July, which would have

dictated a policy of prudence to Stalin.

This end to the war would have left a

bad taste in many mouths. The political left in the west would have railed

about the betrayal of the

The legacy of betrayal could only

have served to make the post-war world more dangerous than it actually was. The

Soviet Union, faced with a resurgent, psychologically undefeated

These crises might have been

containable, but it is unlikely that the world would have been as lucky as it

actually was, in October 1962, when the Soviets deployed missiles to