Camp O'Donnell

|

|

Page 1 |

The Japanese took us off the train

at Capas and we walked about seven miles to

The Japanese took us off the train

at Capas and we walked about seven miles to

Did these Japanese soldiers speak English?

Most of them didn't. Some Japanese noncoms had been educated in

When you were on the march or on the train, did the Japanese ever come up

and speak to you personally?

Not to me or to anyone in our group that I know of.

Did you have any chances to "snow them" or pull something over on

them?

Everybody tried to do that whenever they could. For example, I was an airplane

mechanic and flight engineer before the surrender. After we were captured, I

became a clerk. You would be surprised how many clerk typists we had! A few of

our guys actually collaborated with them and fixed airplanes. Everyone else

shunned them.

I'm sure they did. Were there any nicknames for the guards?

The nicknames I remember were: "The Scarecrow," "The One-Armed

Bandit," "The Snake," and "The Toad." There were

others, but I don't recall what they were.

Making names up and using them gave us a laugh once in

a while. Some of the guys would even bow and smile to Japanese guards and say,

"Good morning, shit face!" Most of the Japanese guards didn't

understand English, but you still had to be careful. If you said something about that Japanese so-and-so

and they heard and understood it, look out!

You arrived at Camp O'Donnell in May 1942.

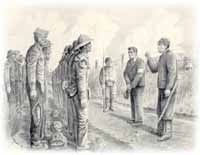

Yes. When we arrived, the damn Japanese commandant, who was nicknamed "The

Scarecrow," was a real SOB.

He made us stand in the hot sun for

two hours. They had built a platform by the camp gates just for him so he could

be above everyone else. He would stand on that thing and give a long harangue

to all arriving POWs. He would say we were not recognized as prisoners of war.

We were nothing! The Japanese were going to fight this war for a thousand

years. Of course, that was all we needed to hear!

He made us stand in the hot sun for

two hours. They had built a platform by the camp gates just for him so he could

be above everyone else. He would stand on that thing and give a long harangue

to all arriving POWs. He would say we were not recognized as prisoners of war.

We were nothing! The Japanese were going to fight this war for a thousand

years. Of course, that was all we needed to hear!

THE VANQUISHED SPEAK

Here on this sun-scorched hill we laid us down

In silence deep as it sit silence of defeat

Upon our wasted brow you placed no laurel crown,

But, neither did you sound the trumpet for retreat

Mourn not for us for here defeat and victory are one;

We can not feel humanity's insidious harm;

The strive with famine, pain, and pestilence are done,

Our compromise with death laid by that mortal storm

Though chastened, well we know our mission is not dead,

Nor are the dreams of victory in vain.

For lo, the dawn is in the east: The night is fled

Before an August day which will be ours again:

So rest we here, dear comrades, on this foreign hill,

This alien clay made somehow richer by our dust,

Provides us with a transitory couch, until

The loving hills of home enfold us in maternal trust,

For we are assured brave hearts across the sea will not forget

The humble sacrifice we laid on Freedom's sacred shrine,

And hold that righteousness will be triumphant yet,

And o'er the Earth again His star of Peace will shine.

Dedicated to those who died at Camp

O'Donnell Prisoner of War enclosure in the Philippine Islands by Fred W. Koenig

1st Lt U.S.A.

Camp O'Donnell

|

Page 2 |

To make things worse we started hearing hair-brained rumors on a daily basis. They

were flying everywhere, mostly from people who came back to the camp from work

details. They didn't actually see what things the rumors were about. They were

just hopeful they would happen.

What were some of them?

For example, someone would come in and say, "There is a Red Cross ship in

the harbor with food," or "There is another ship in the harbor and we

are going to be exchanged," or "We are going to be repatriated very

soon." These rumors were really rough on morale.

Some soldiers believed them and died because nothing happened. If you listened

to all that malarkey, you would go insane. I started to pay attention to them

and they got to me. That's why I wanted to get out of there. I said, "I'm not going to stay here and take

this."

What was the camp like physically?

What was the camp like physically?

There were long bamboo huts and one spigot of drinkable water for the entire

camp, which held about 7,000 Americans. We would line up once a day and get

water. One man was usually designated to get as many canteens as he could

possibly carry, go to the spigot, and fill them up. When they wanted to harass us, the damned Japanese

would shut the thing off for no reason! They would leave it off for hours at a

time. You would have to stand there and wait for them to turn it on again.

How were the Japanese behaviorally on a day-to-day basis?

We had to acknowledge every single Japanese from the

lowest to the highest. You didn't salute them like we did in our military. You bowed. And you better bow! They would club you if

you didn't, especially the privates and privates first

class. Those who didn't bow found out in a hurry that they better do it.

Other than that, they left us

strictly alone. Eventually, we were able to set up mess halls.

Other than that, they left us

strictly alone. Eventually, we were able to set up mess halls.

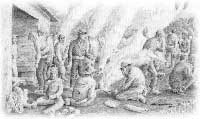

What would you eat, and how often?

We cooked rice we called lugao. We ate once a day,

usually at noon. Everyone got a cup of that gruel. It was rice that was thinned

out with water so you could pour the stuff.

You were fed once a day.

Did you get anything besides water to drink?

No.

Camp O'Donnell

|

Page 3 |

|

Could you find anything else?

Could you find anything else?

No. We were confined to this area and there was nothing there. Everything had

been stripped before we came. That's

why people were dying so fast. There were no medical facilities whatsoever.

People who needed some type of medical treatment didn't bother to go to the

so-called infirmary. There was nothing

to treat you with. If you got real bad you were put in the death ward. Those who

went there stayed until they died.

Did you have American doctors?

We had American doctors, but they had no facilities and absolutely no medical

supplies.

No bandages?

Nothing.

No antibiotics or ointment?

No.

They just did the best they could.

On the march, the Japanese had stripped

the doctors of everything. They took everything from us! The

Filipinos had it worse than we did. We were separated from them. They had to drink polluted water. Those poor

Filipinos died like flies! The Japanese saw they had to do

something. They started pardoning them so they could go home.

Where did you sleep?

There wasn't enough room in the barracks for everyone. If you weren't in a

barracks, you slept right out in the open. If it rained, you got wet!

What did you do all day?

Nothing. You couldn't look for food because there was

no food! Everyone got together in small groups with people they knew before the

surrender. I hung around some individuals who had been in my squadron at

Nichols Field. There was not much talking because there was nothing to talk

about.

To put it in modern-day terms, you "hung out."

That's about the only way you could describe it.

Were you free to move about the camp?

In the compound, yes. There was a string of barbed

wire around the whole place and it was loosely patrolled. You could have gotten

out any time but where would you go? Without outside contacts, you were a dead

duck.

The Japanese would shoot anyone who went beyond the wire?

Yes. They also offered a 100-lb. sack of rice to any Filipino that would turn

in an escaped prisoner.

The Filipinos were hungry and would do it?

That's right.

Could you sleep during the day?

You could sleep all day and all night if you wanted to.

Did the Japanese bother you?

No. We just existed. You hung out and didn't overstep the boundaries. We tried

to keep things as clean as possible. Occasionally, we would dig a slit trench

for toilet facilities. A slit trench is a long trench you straddle and go to

the bathroom in.

There was no privacy! Once the trench was full, it was covered up and we dug

another one someplace else. But I hated

it there! I said to myself, "I gotta

get out of here" because of all the rumors flying around. The Japanese

told our officers they were forming a detail. I volunteered and was selected

along with about two hundred other men. I didn't know what the detail was and I

didn't care. Luckily, I was sent to Clark Field. I was very thankful because it

got me out of